SMECO keeps its transformers sustainable

The cooperative recycles old devices and tests them for toxic chemicals that may be inside.

SMECO is committed to building a more sustainable future for our community and our planet. As part of caring for the environment, we recycle transformers that have been taken out of service, and we test them for toxic chemicals that may be inside.

Keeping chemicals

out of the environment

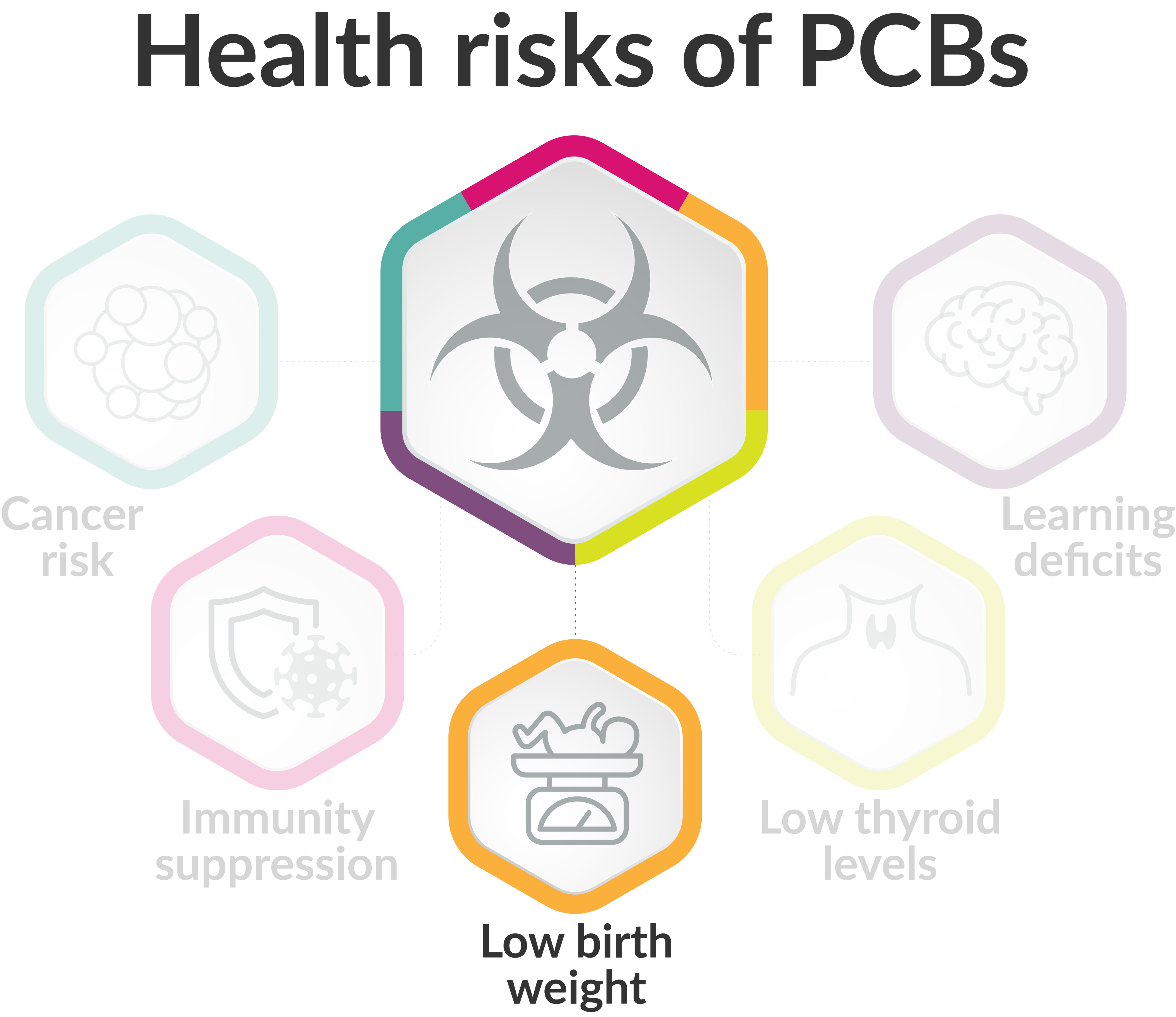

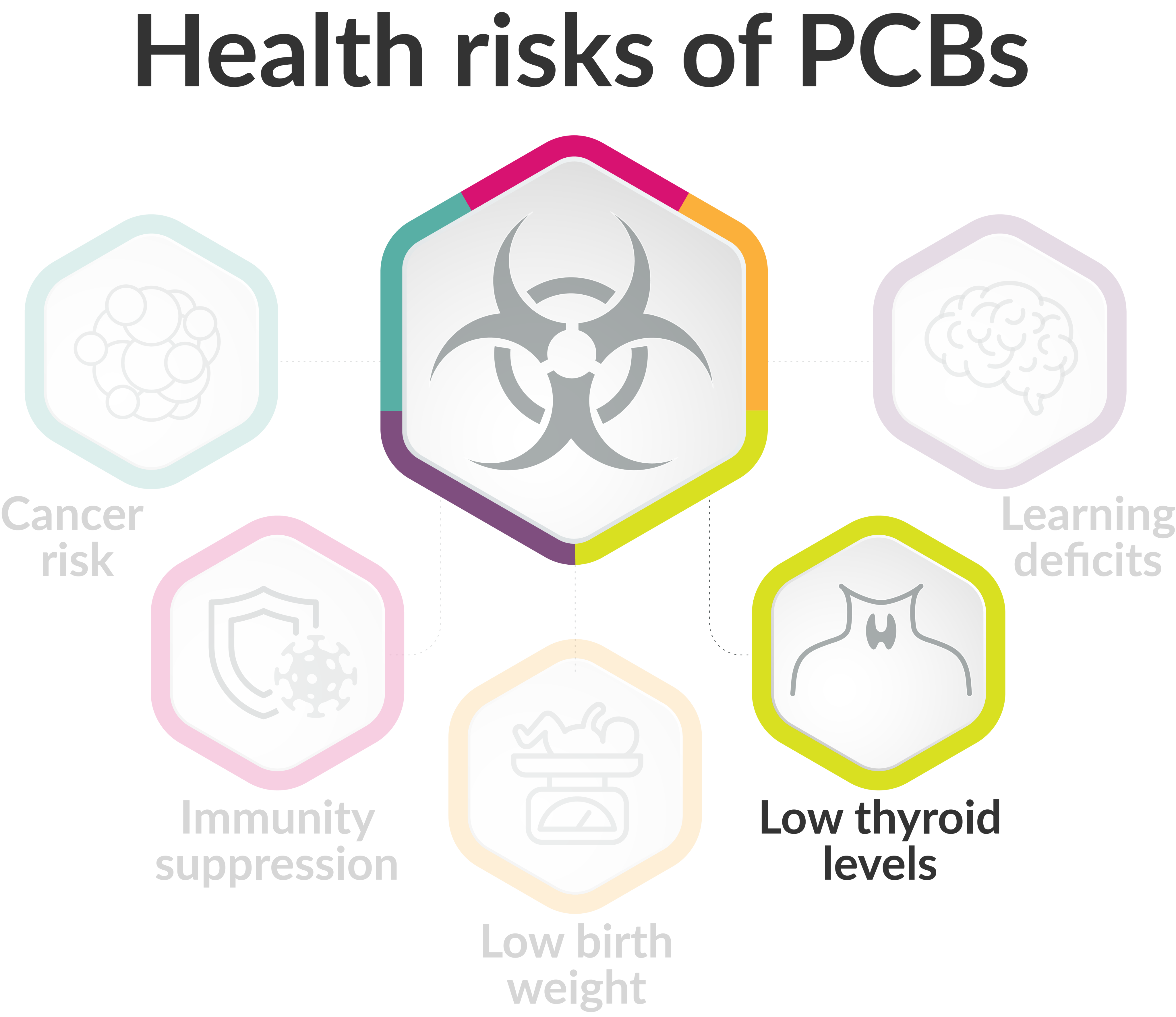

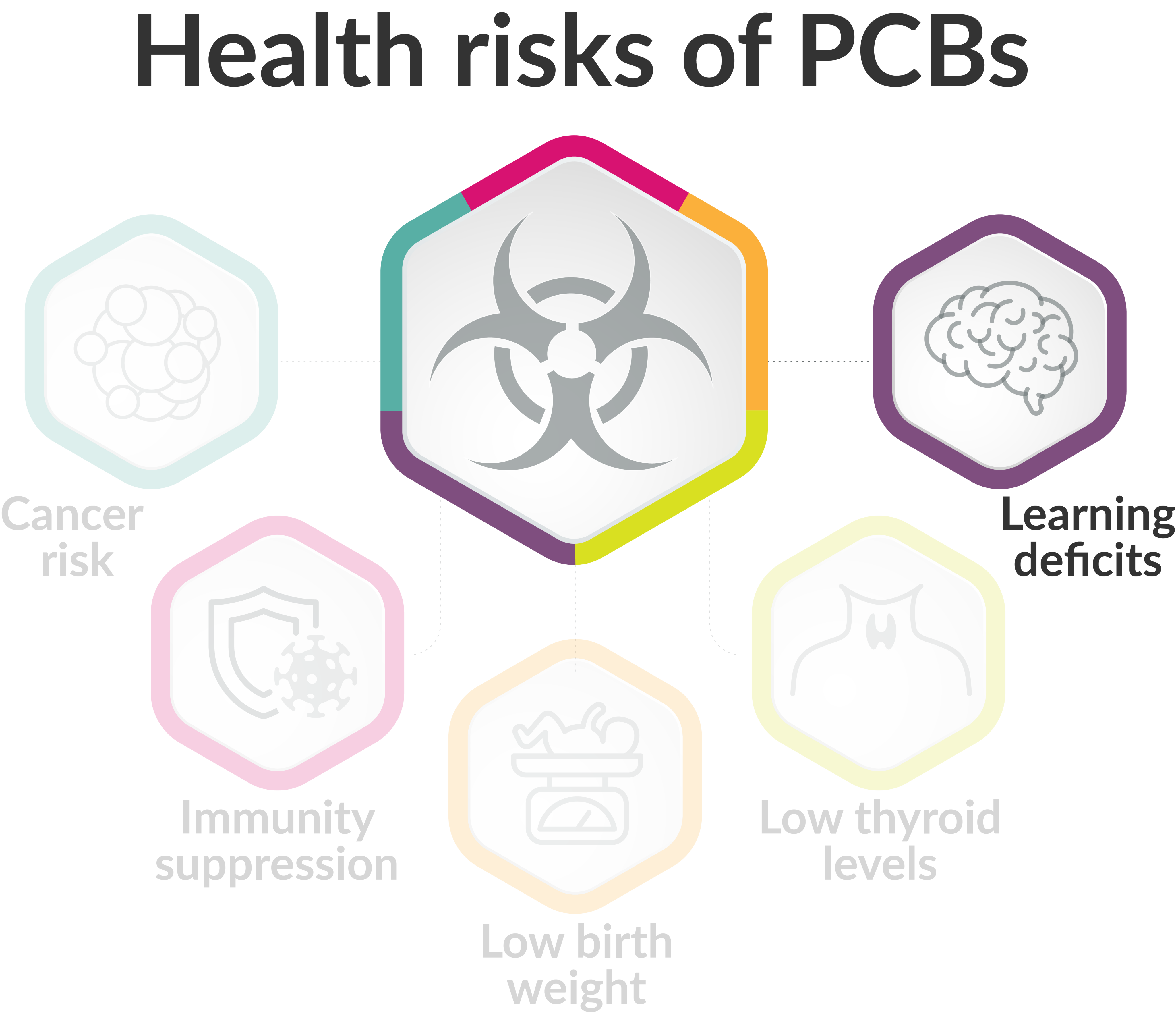

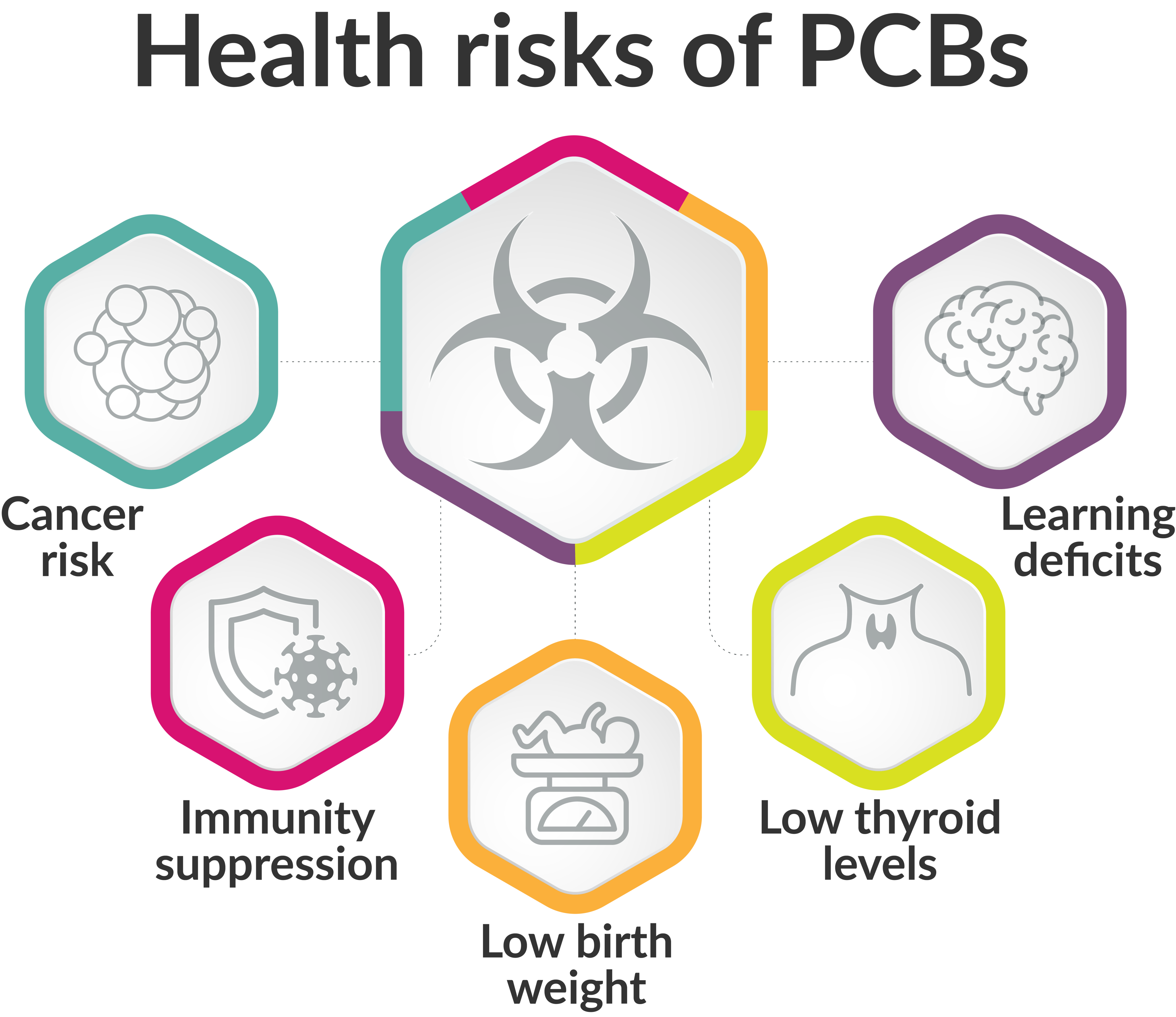

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

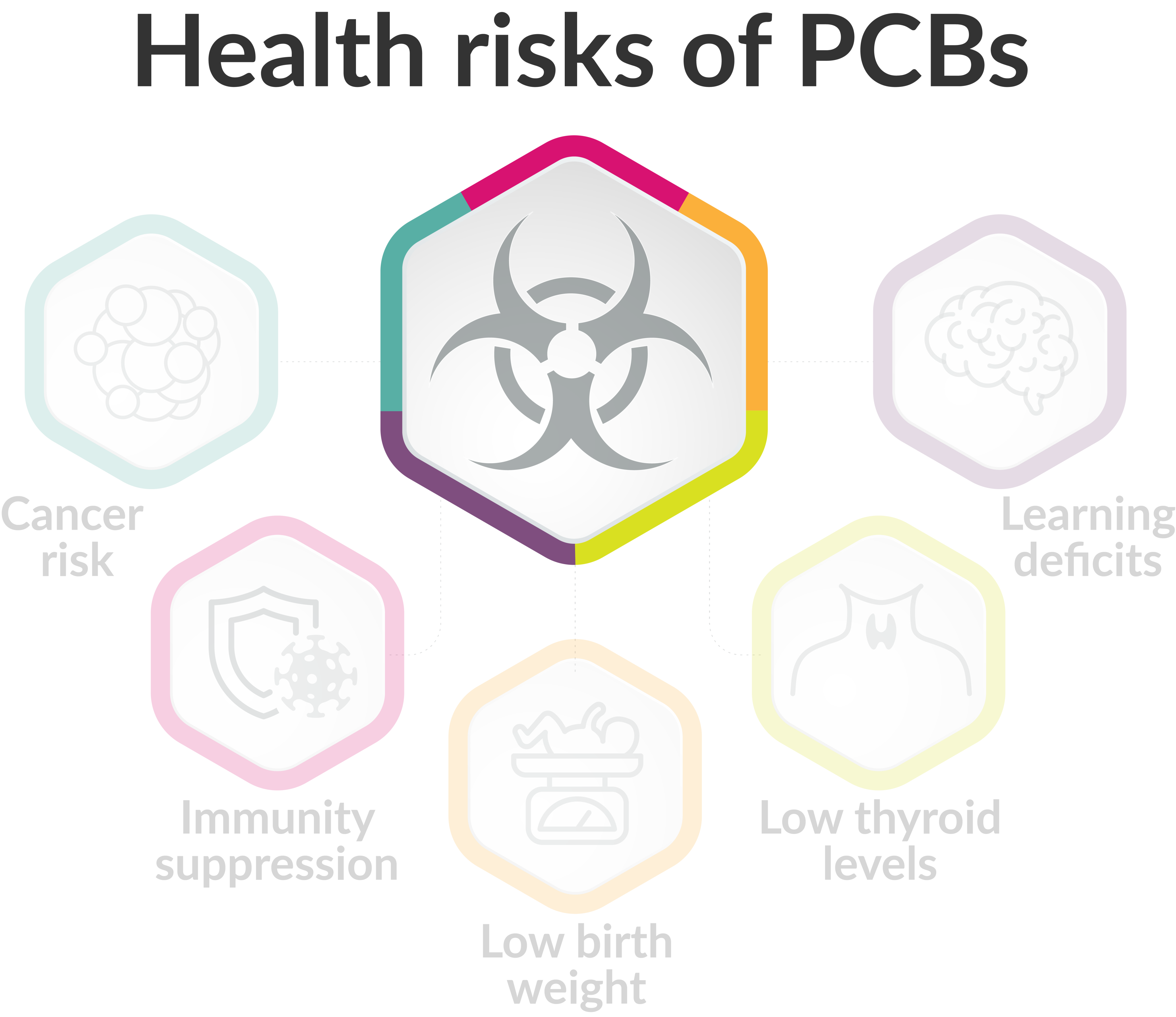

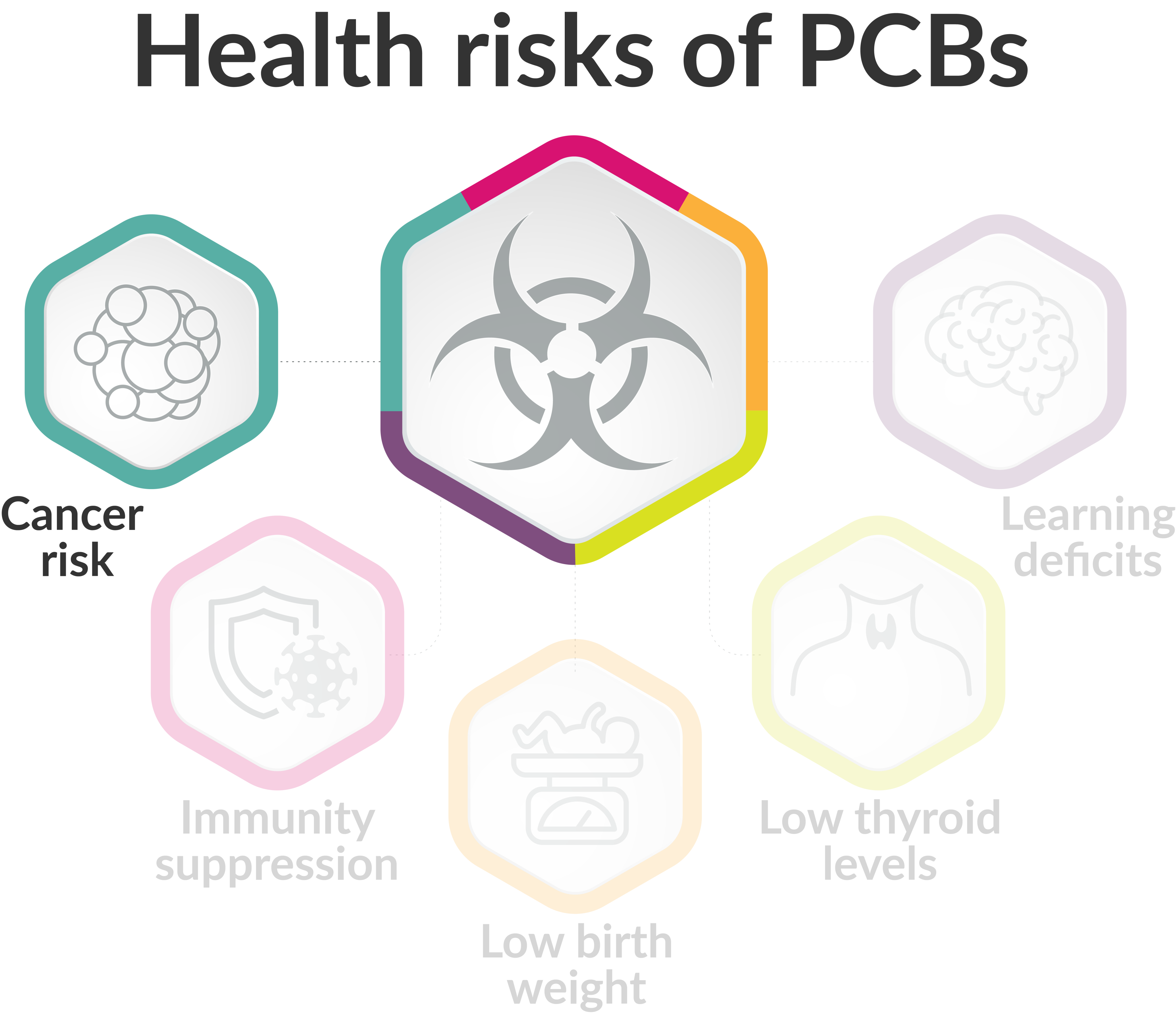

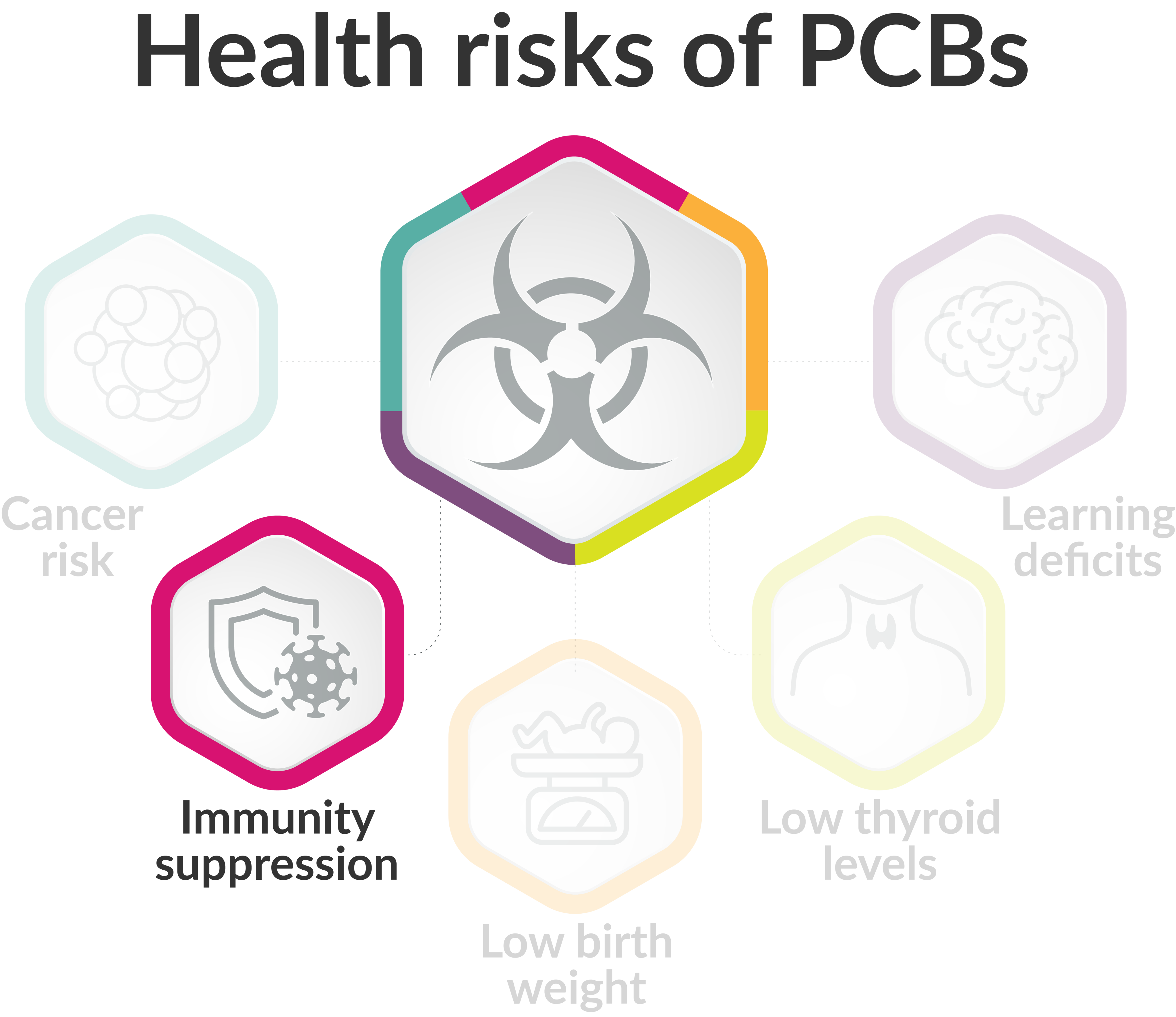

During the 20th century, manufacturers of transformers and other electrical equipment often used polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) as an insulating fluid. Because of the chemicals’ non-flammability, chemical stability, high boiling point, and electrical insulating properties, PCBs had hundreds of industrial and commercial applications. They were later found to pose risks to human and animal health because of their toxic and bio-accumulative properties. The toxic chemicals were found to persist for many years in the environment, leading the United States government to ban their production in 1979.

If an overhead transformer made before the ban is still functioning, it can remain in service as long as its metal case does not leak oil.

“It’s beneficial not to have potential sources of PCBs on our electric system,” said Tommy Short, SMECO's managing director of environmental and property rights. “Many of the old transformers are still working fine, but the potential for contamination is still there. Our preference is to remove and replace these units.”

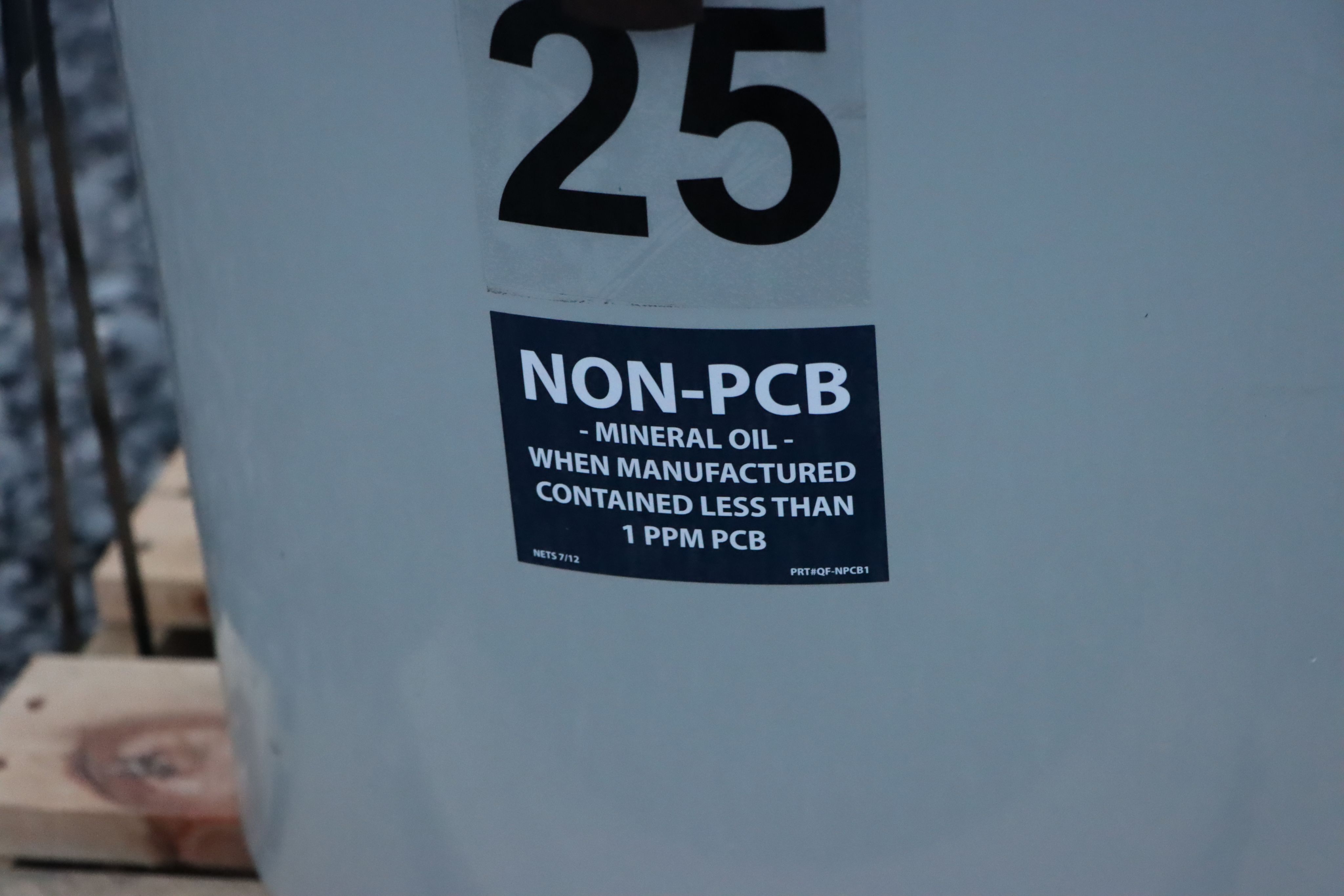

The cooperative's newer transformers contain mineral-based insulating oils, which are less toxic to humans and the environment. If the transformer is close enough to a residence, fire safety codes may require synthetic ester oil, or natural ester oil derived from vegetable oils, which have higher fire safety ratings.

A discarded transformer made before 1979 bears a warning label for PCBs. This unit will be sent to a facility that will safely and properly decommission the chemicals.

A discarded transformer made before 1979 bears a warning label for PCBs. This unit will be sent to a facility that will safely and properly decommission the chemicals.

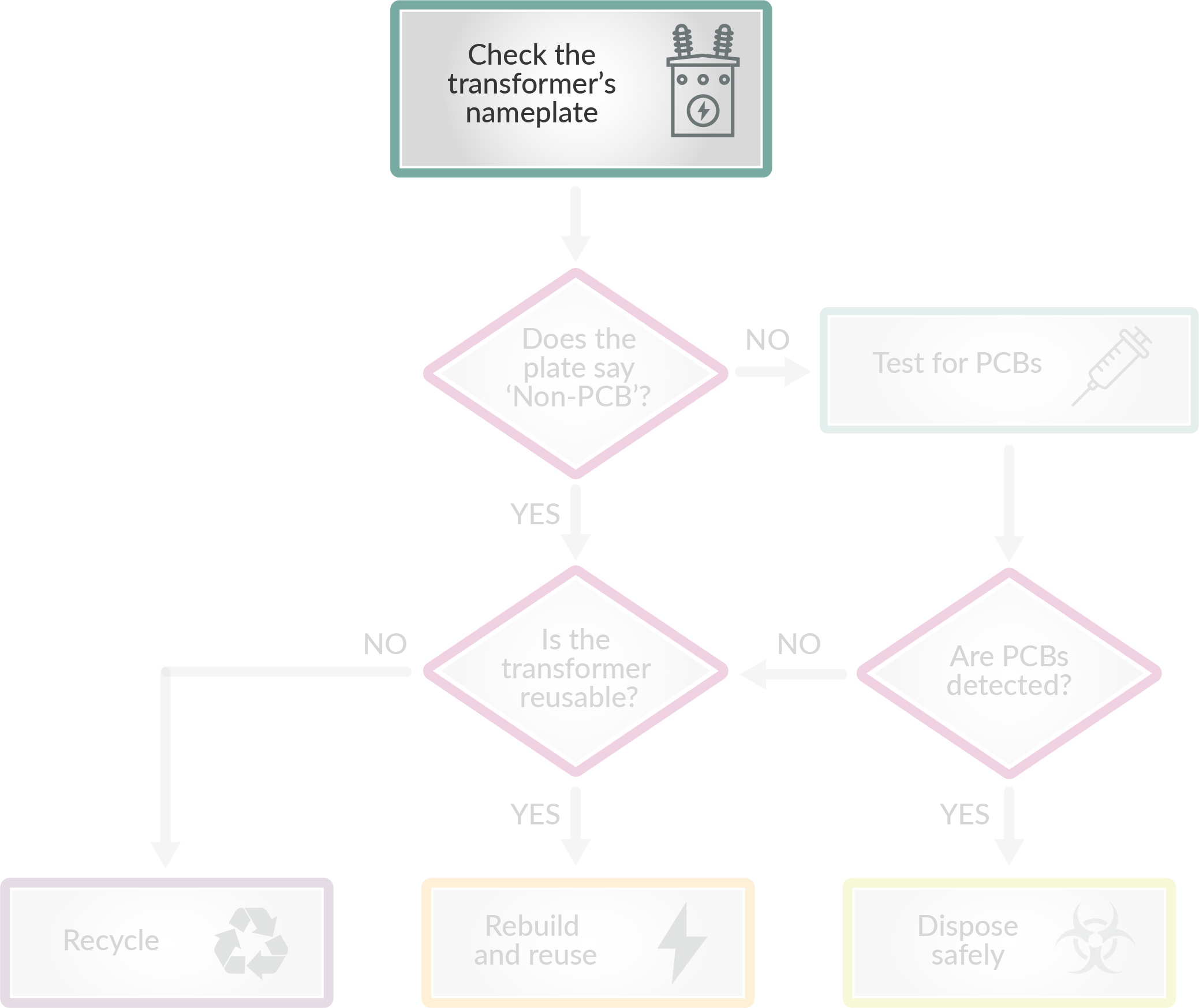

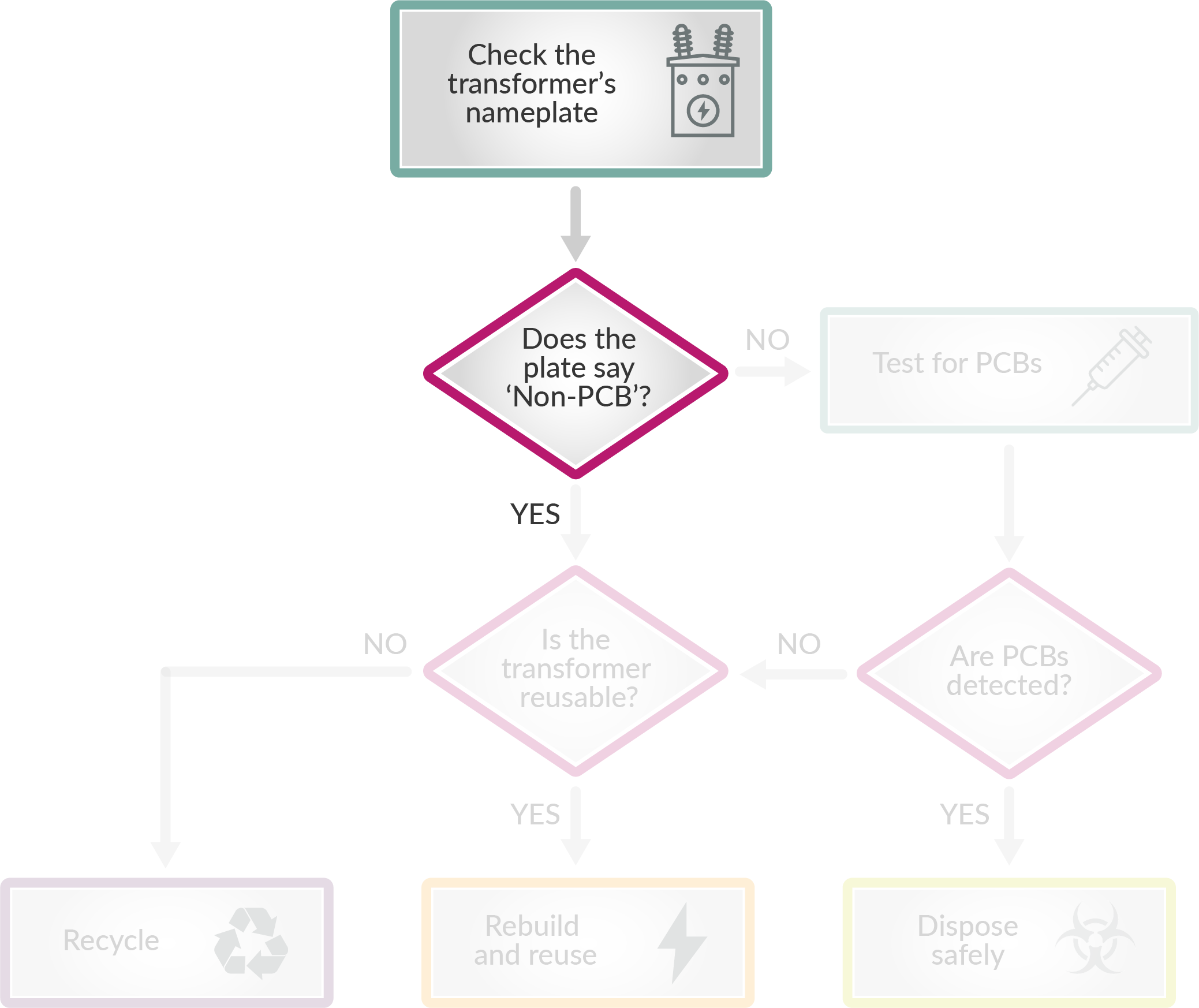

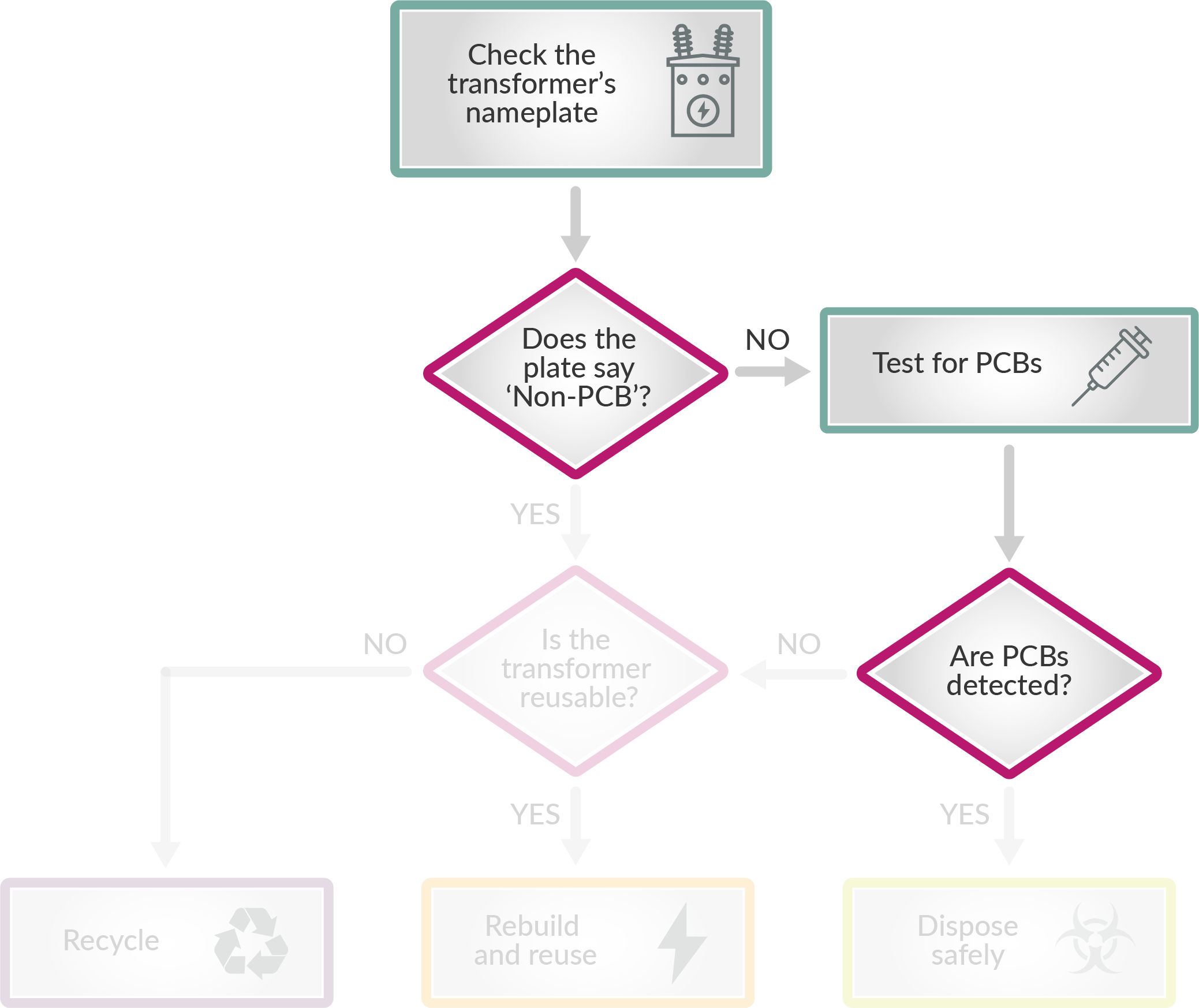

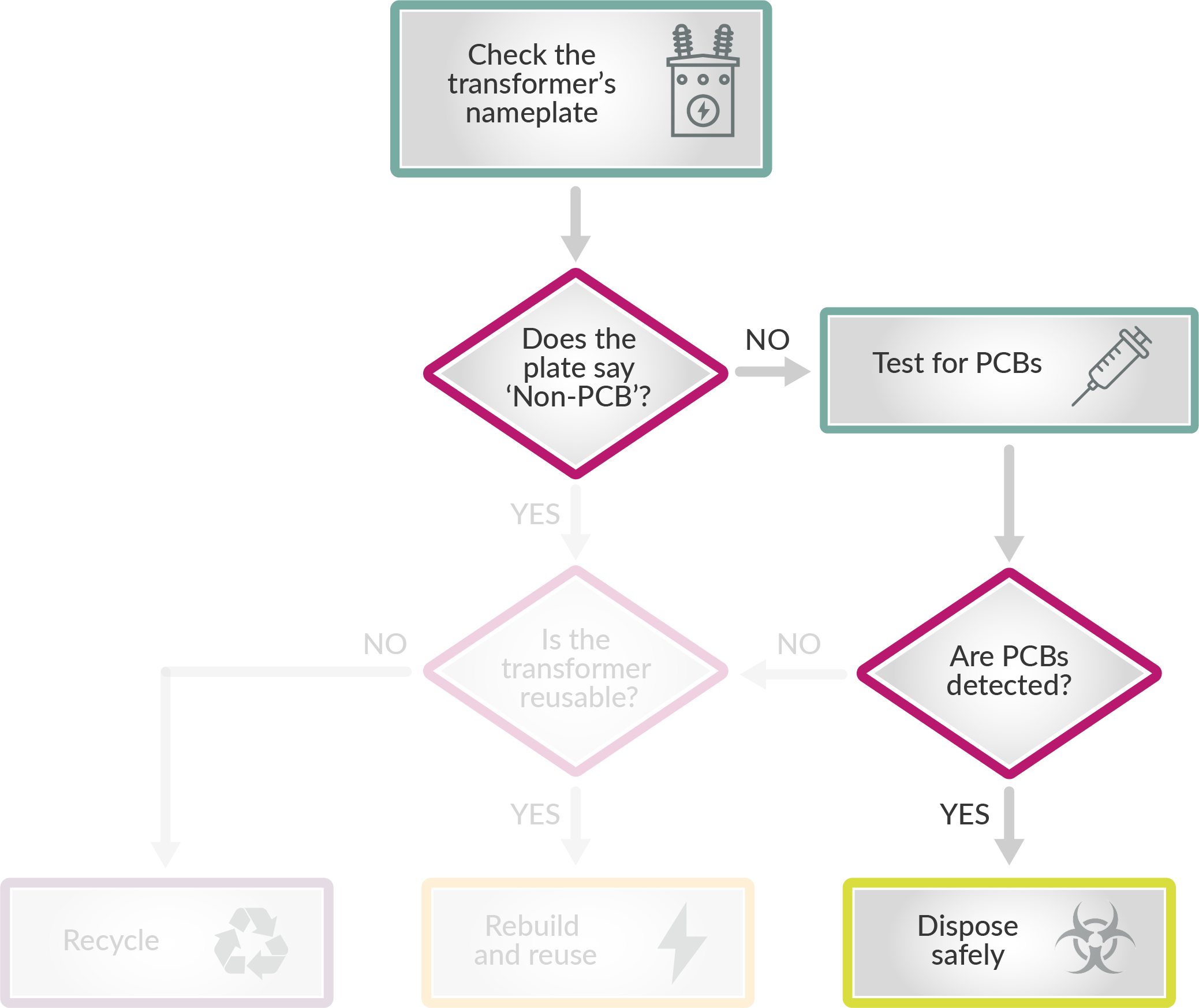

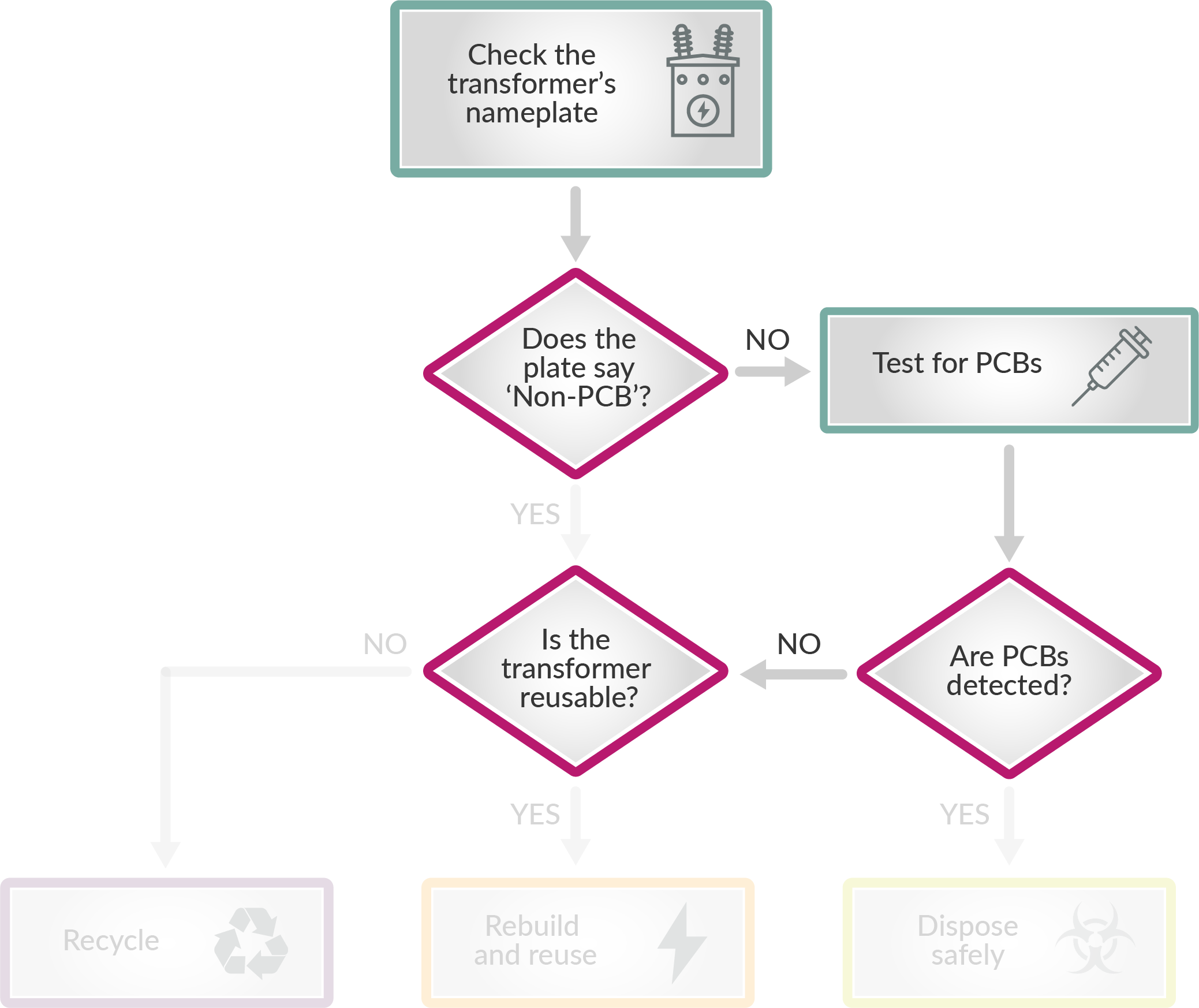

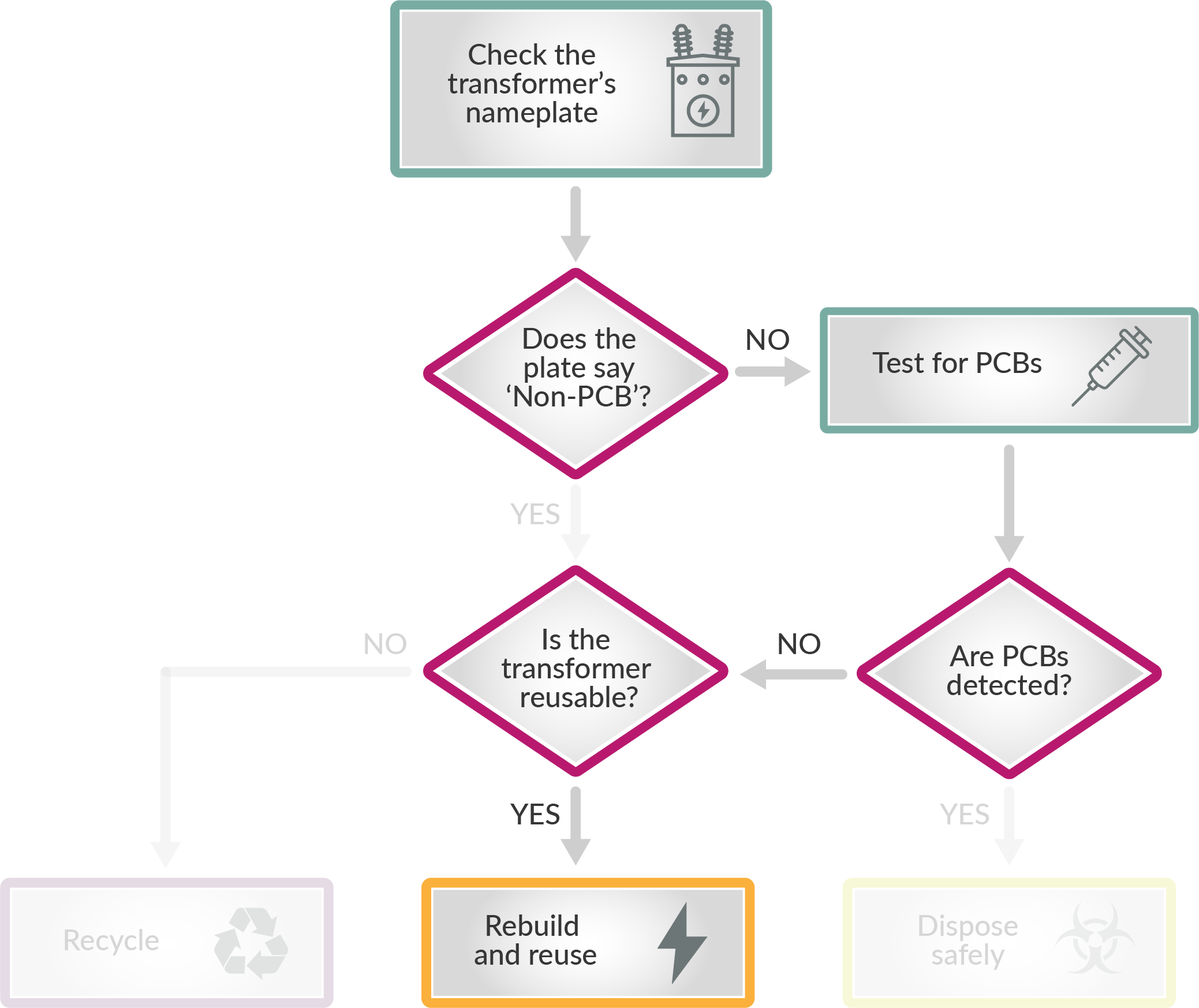

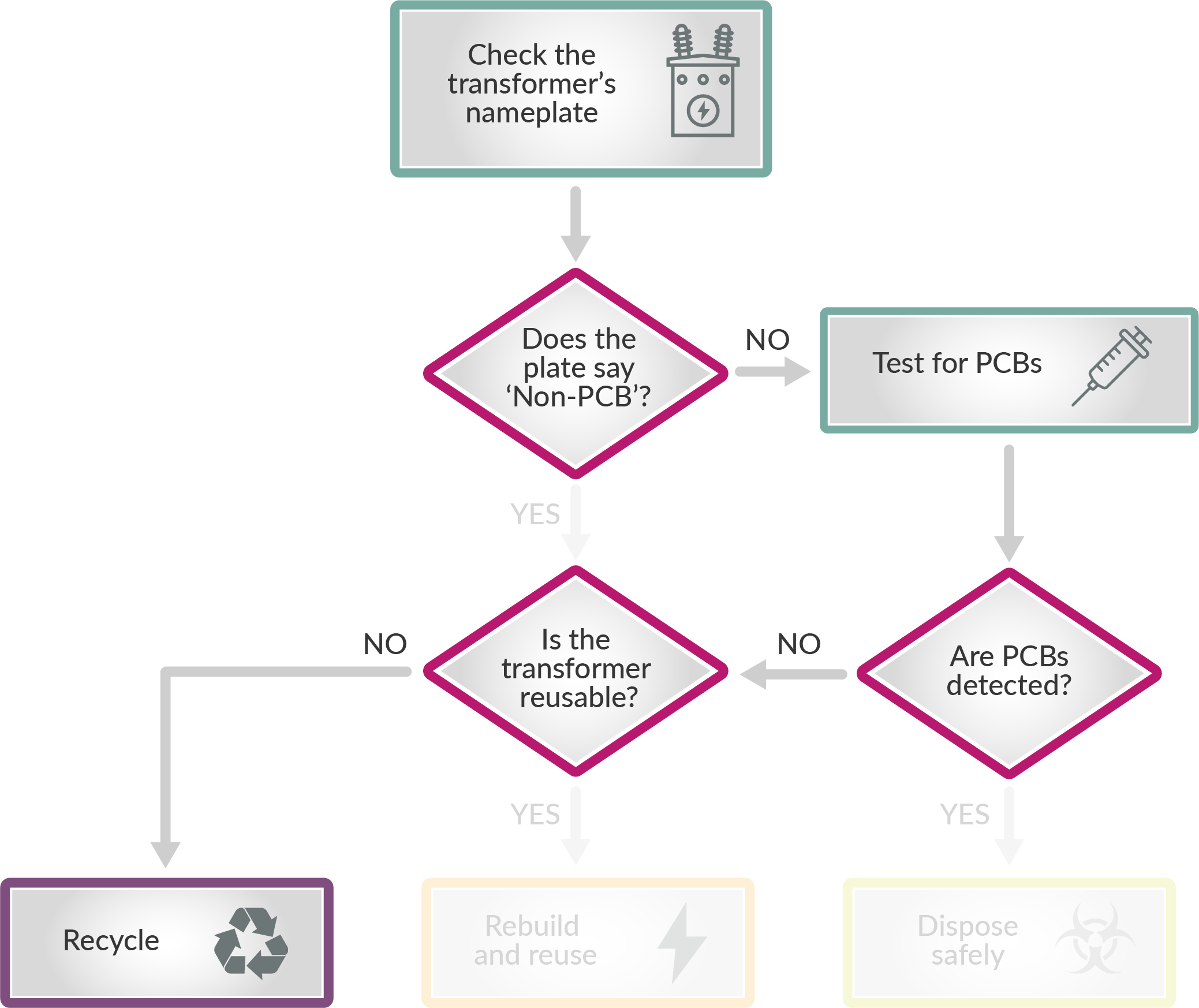

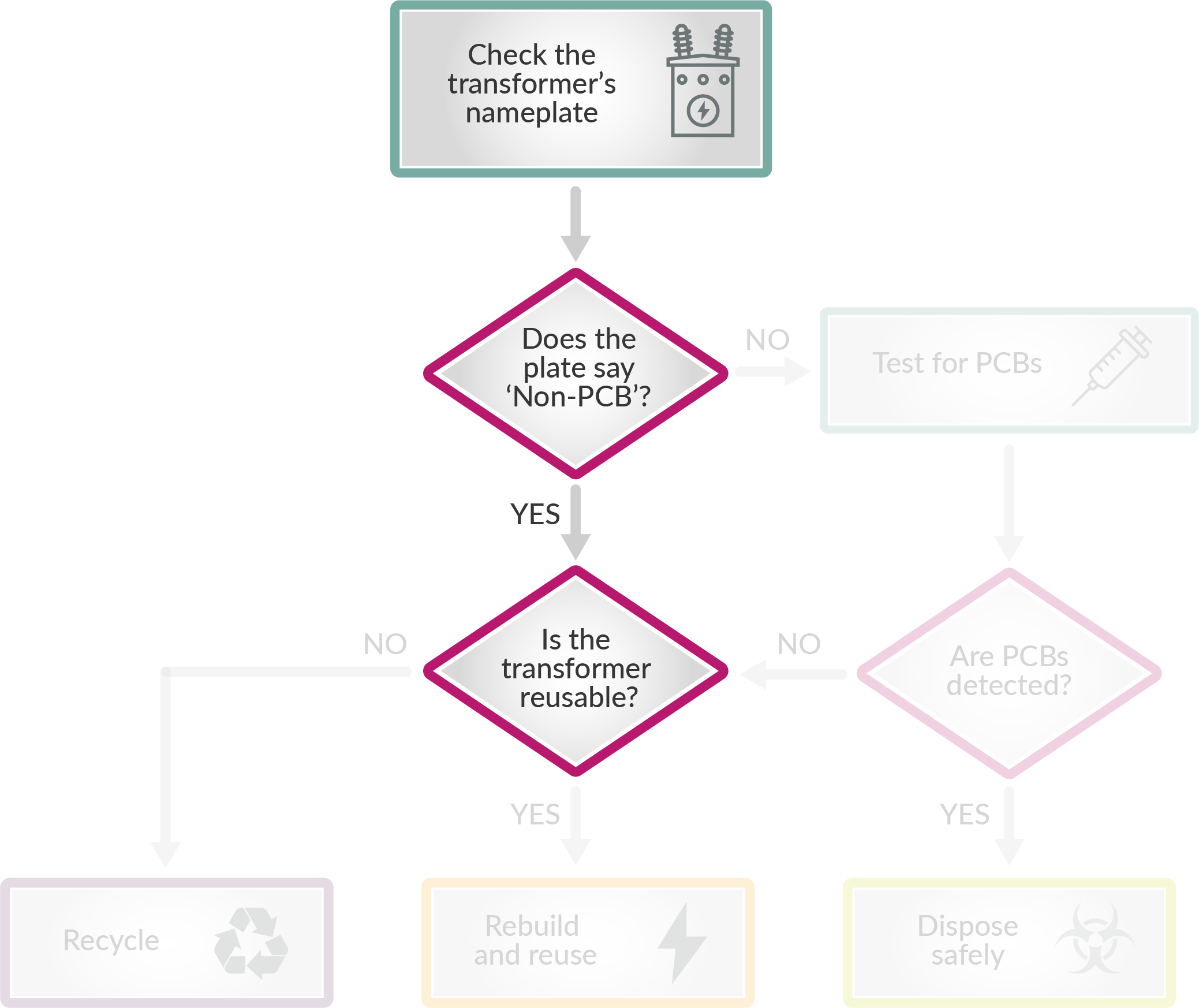

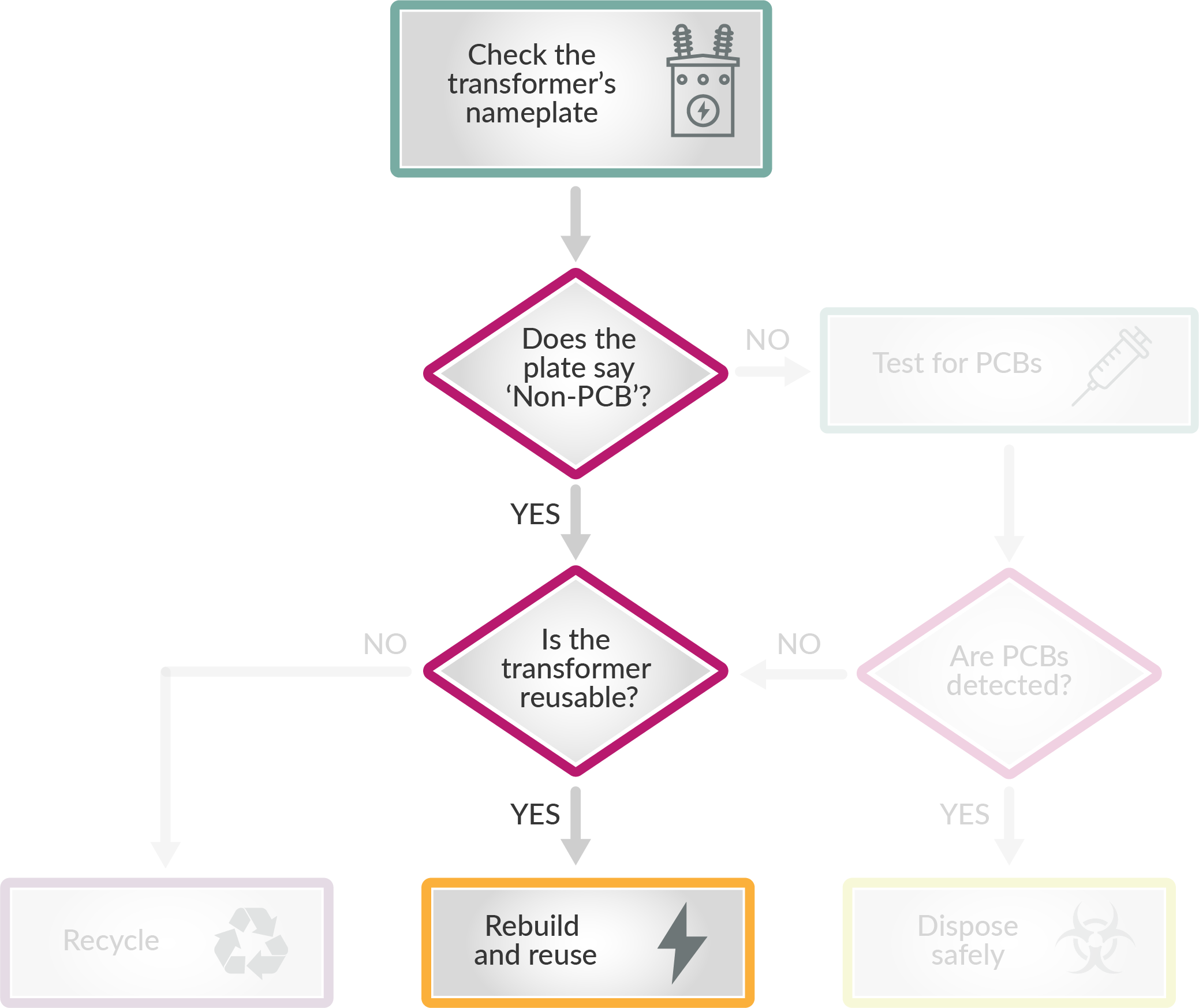

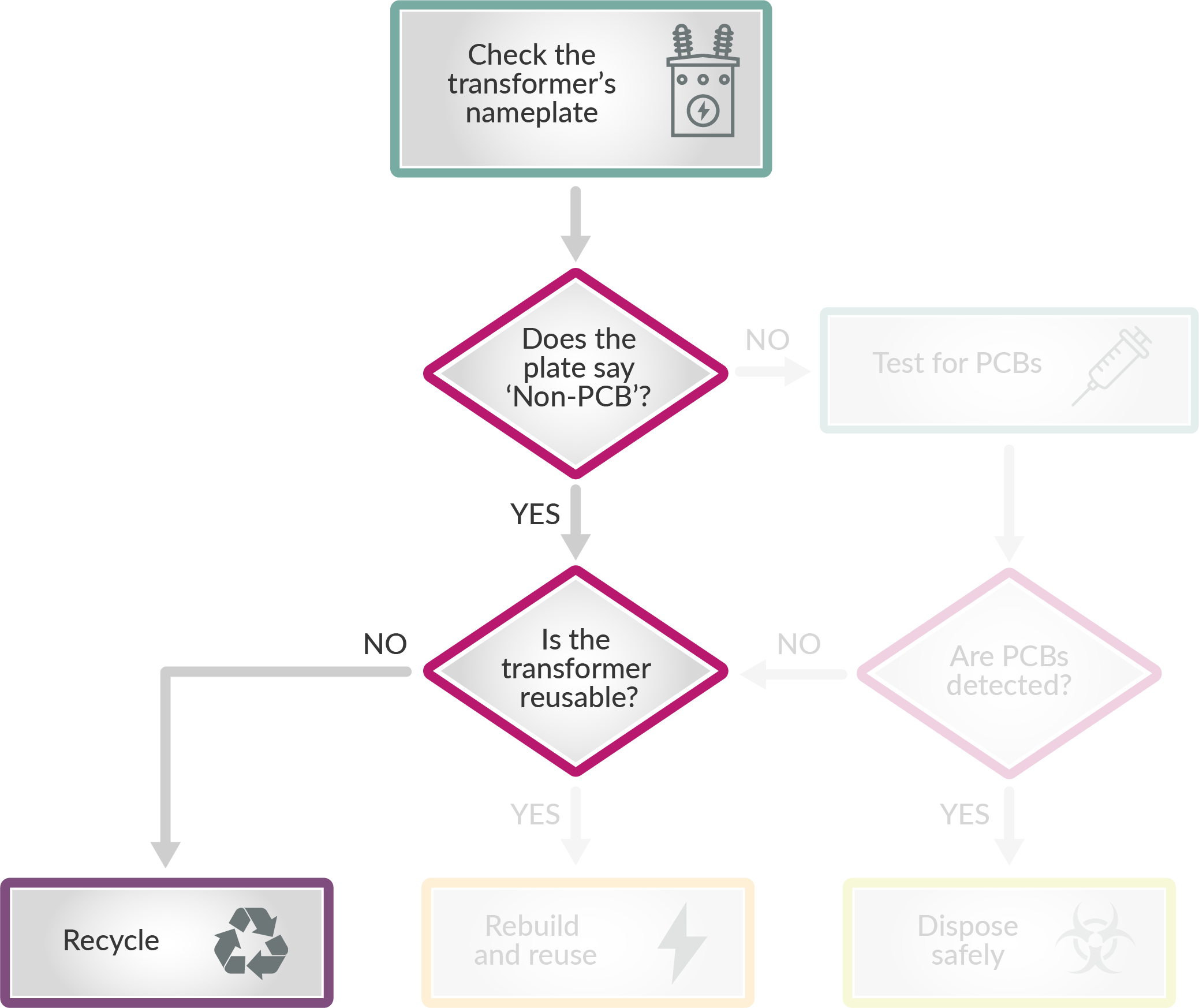

When SMECO replaces a transformer on its system, the unit’s manufacture plate is checked for its PCB content. If the nameplate doesn’t clearly state that the unit is filled with non-PCB insulating fluid, it is tested for PCBs.

A new process for

transformer disposal

Late in 2022, the cooperative hired a new contractor to dispose of old transformers. Instead of carrying away potentially contaminated units for testing, G&S Technologies collects oil samples in SMECO storage yards in Hughesville and Leonardtown. The vendor’s representative punches a tiny hole in the top of the transformer and uses a syringe to pull a sample to test the transformer oil for traces of the chemicals. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency deems the oil as PCB-contaminated if the level is 50 parts per million or higher.

Once the results come back, G&S picks up all of the units for disposal. Non-PCB units head for the company’s New Jersey plant for recycling or rebuilding. The PCB-contaminated units go to their sister facility, TCI in Alabama, which safely and properly decommissions the chemicals, mainly by incineration.

A contractor for SMECO uses a syringe to collect a sample of insulating oil from an old transformer.

A contractor for SMECO uses a syringe to collect a sample of insulating oil from an old transformer.

If a newer transformer has no label indicating its PCB content, it undergoes the same testing as the older units.

“Any transformer made after the ban should not contain PCBs, but if it’s not clearly labeled, then we have to assume PCBs until we get the test results back,” Short said.

Testing on site protects both SMECO and the environment. Under federal rules, a retired transformer is still officially in service—and still the utility’s responsibility—until the unit arrives at the testing facility.

“If we sent out the transformers untested, and the truck was in an accident, we would be responsible for knowing what is on the truck and cleaning it up,” said Grayson Jenkins, environmental affairs coordinator in SMECO’s Southern Region. “If any of the oil leaked, we would have to treat all the transformers and oil as PCBs.”

Our new process alleviates this risk now that we test the unlabeled units before they leave. The transport truck must have a six-inch lip around the bed for spill containment, which is another required measure for risk reduction.

For transformers labeled as non-PCB, the recycling and disposal process is more straightforward. G&S ships them to its plant, drains the oil, and removes the copper and other metals. The company rebuilds any transformers that are still usable, and sends them back to SMECO to be put back into service.

“The cost of rebuilding a transformer is significantly less than buying new due to the current supply chain issues, so we save money,” Jenkins said.

“They are a one-stop shop for us,” Short said. “It’s amazing how fast our storage yards fill up, and it’s nice to see the whole process working smoothly and efficiently. They help keep our yards clean and uncluttered.”

Cleaning Up After Oil Spills

Tommy Short lays down clay to absorb spilled transformer oil after a vehicle accident topples a utility pole.

Tommy Short lays down clay to absorb spilled transformer oil after a vehicle accident topples a utility pole.

SMECO's precautions against PCBs also apply to leaks from transformer oil, often after a vehicle collides with a utility pole or pad-mount transformer. When the Environmental team arrives at a spill site, they immediately take action to stop and contain the oil leak. The team also manages the clean-up efforts to remove all contaminated dirt and debris. and collect it into drums. Then they draw an oil sample for G&S to test for traces of the toxic PCB chemicals. G&S disposes of the collected drums of material in an appropriate manner, depending upon the PCB content.

SMECO sees an average of two oil spills per week, due mostly to the frequency of vehicle collisions with utility poles.

“Every spill site is different and containment and clean-up efforts can be challenging. But it’s imperative that we do everything we can to remove all oil-contaminated soil and debris from the environment, both PCB and non-PCB. The Environmental team works diligently to ensure SMECO is in full compliance with all laws and regulations, which includes reporting spills to the Maryland Department of the Environment within two hours from when the spill occurred,” Short said. “If you see a spill, please report it to us and we will be ready to respond.”

To report an oil spill from a transformer, visit the SMECO website.